Book Scanning: The Hard Way

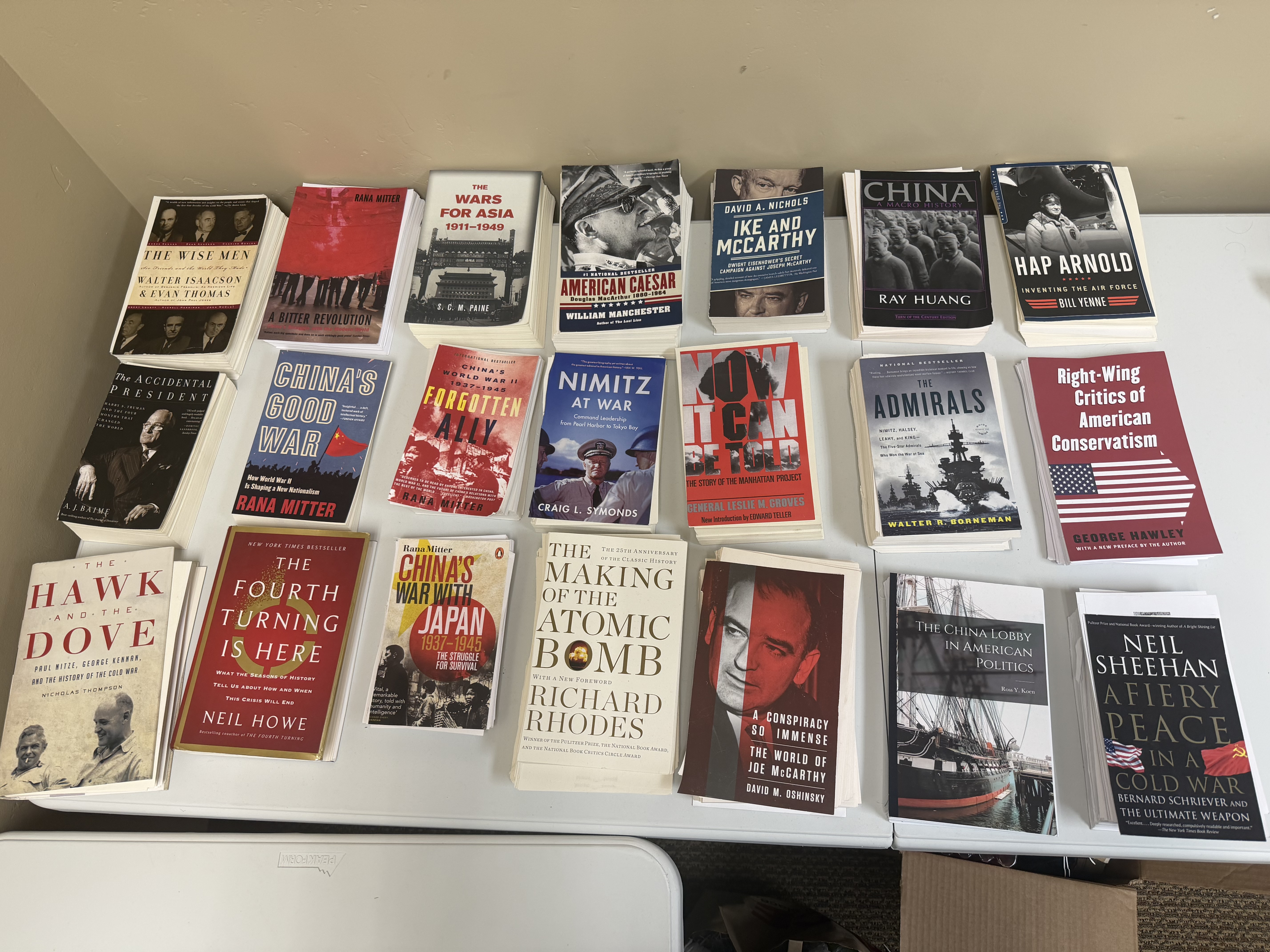

I’m a HUGE audiobook fan. I listen while cooking, hiking, before bed, etc… I’ve got almost 5 months of listening time on Audible. But as I’ve discovered over the years, not every book is available as an audiobook. Military history, academic texts, out-of-print nonfiction/fiction—if you want to listen to them, you have to make them yourself. This desire to own the means of production has slowly but surely led me down the rabbit hole of book scanning.

I tried the obvious path first. Got a CZUR overhead scanner and a Speechify subscription. Scanned “China: A Macro History” by Ray Huang—300 pages. I tried scanning it after work one day. I thought it would be quick! Boy was I wrong. It took a few practice attempts over a weekend to get a good “clean” scan of the whole book. Curved pages, glare from the binding, misaligned pages, all made it hard to get a good result. After a few hours of work, I had a PDF that looked decent.

Speechify’s OCR caught most of the words, but that’s not enough. Page numbers read aloud. Running headers interrupting every page. Image captions scattered through the text. Footnote numbers with no footnotes. The result was technically an audiobook, but not one you’d want to listen to.

I shelved the project.

Round Two#

A few months later as I was reading a series of WWII general biographies, I kept finding more books I wanted to listen to: S.C.M. Paine’s “The Wars for Asia” and the classic “The China Lobby in American Politics.” So I was back to the scanning problem.

The way I had come to understand the issue is that while OCR is quite good and so are scanners to get something of the quality of an Audible audiobook (i.e. no user discernible issues) was something else entirely. Those audiobooks have been professionally produced with human editors. Getting something close to that quality with consumer hardware and software, with little to no human intervention, appeared to be an unsolved problem and a fun challenge!

Consumer scanners like CZUR are cameras with software dewarping. Fast, but the image quality has limits. For better scans, you need either expensive hardware or a different approach.

The Destructive Path#

If you’re willing to sacrifice the physical book, the quality problem is solved. Cut the spine off, run the pages through a sheet-fed scanner like a ScanSnap iX500, and you get clean, flat, high-resolution images. No curved pages, no shadows from the binding.

It feels wrong the first time you do it. Then you realize the book was $8 used and the audiobook doesn’t exist at any price.

The Non-Destructive Problem#

Non-destructive scanning that matches sheet-fed quality requires serious hardware. Professional overhead scanners from Bookeye or Zeutschel start around $15,000 and go up from there. They use true CCD line sensors instead of cameras, motorized book cradles, and glass plates that flatten pages physically rather than in software.

To buy one, you talk to sales people, get quotes, and schedule an installer to come set it up. It’s enterprise equipment priced for libraries and archives.

The DIY Alternative#

There’s a middle path that mostly died out.

In 2009, Daniel Reetz built a book scanner from trash and cheap cameras because it was cheaper than buying textbooks. He posted instructions to Instructables, launched DIYBookScanner.org, and sparked a community that eventually produced over 350 scanner designs and 2,000 contributors.

The flagship design was the Archivist—plywood frame, plate glass platens, two Canon PowerShot cameras, LED lighting, and a Raspberry Pi running capture software. Materials cost around $300-500. An experienced operator could scan 1,000+ pages per hour. Reetz called it “the VW Beetle of book scanners” and released it into the public domain in 2015.

The community peaked around 2011-2019, then faded. Canon discontinued the compatible PowerShot cameras. The kit suppliers stopped production during the pandemic. Smartphones got good enough for casual scanning. The forums are still up but mostly read-only now.

The Archivist design and some of the derivatives still work if you want to build one. It’s just that nobody’s selling kits anymore, and you’ll need to source your own cameras and parts.

The Real Problem#

Raw OCR gives you text with garbage mixed in—headers, page numbers, captions, footnote markers. To make an audiobook, you need to identify what’s body text and what’s noise. You need to extract the table of contents and link it to page numbers. You need to handle footnotes sensibly. You need to produce something that flows when read aloud.

I’m building a tool called Shelf to solve this. It runs scans through multiple OCR providers, uses LLMs to classify and label the structure, extracts and links the table of contents, and produces clean ePub files. Soon to be open source, and designed for the books that don’t exist any other way.

More on that soon.